“The Whist Players”, the pop story of a trip to nostalgia by the Catalan Vicenç Pagès Jordà that is published again in Spanish

[ad_1]

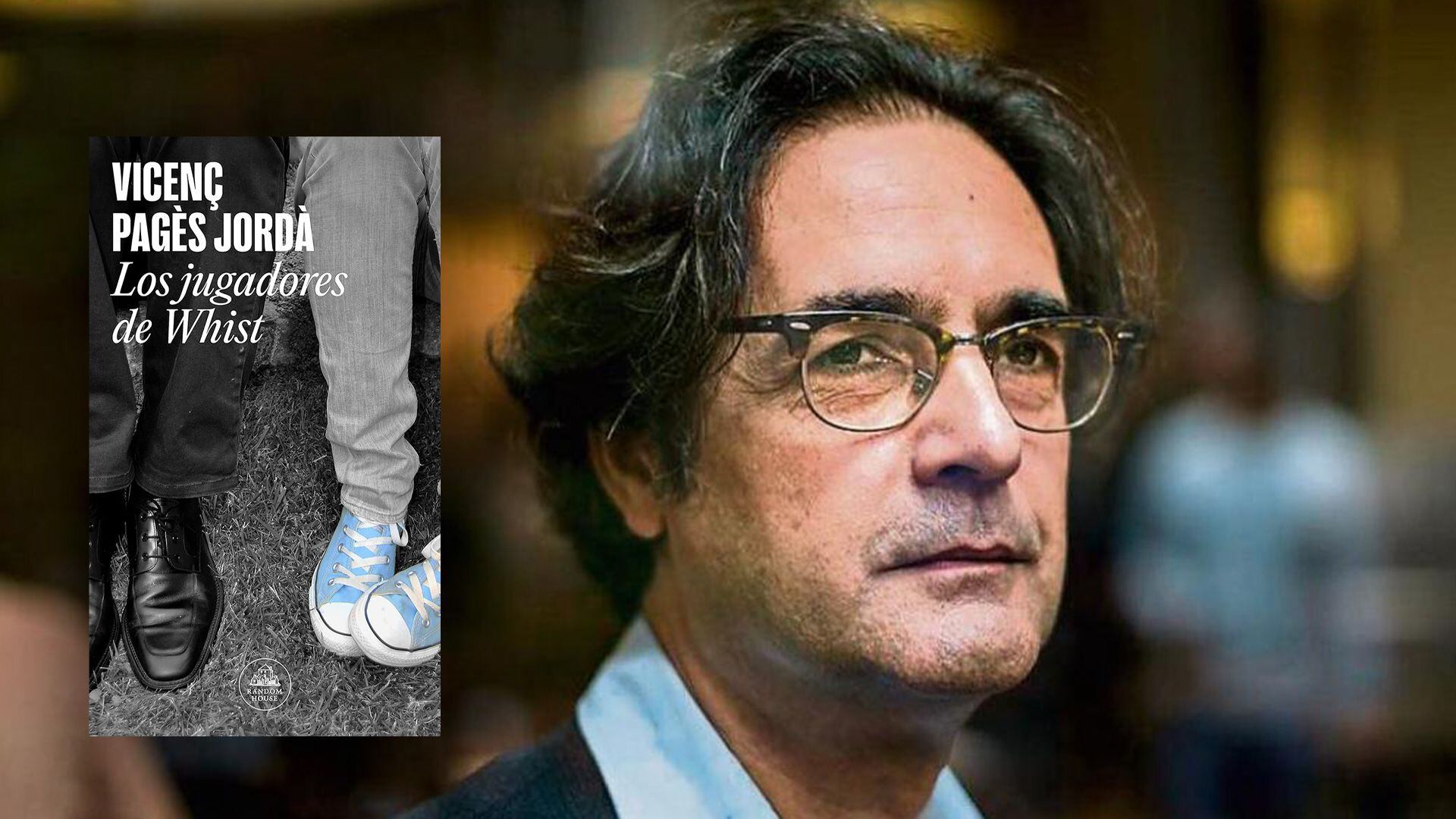

The Spanish subsidiary of Penguin Random House has announced among its October news the publication of the Spanish translation of one of the most notable novels by the Catalan writer Vicenç Pagès Jordà.

Originally published in 2009, this new edition of The Whist Players arrives in bookstores under the care of Argentina Flavia Company, a year after the death of the author and literary critic.

Born in Figueres in 1963 and died in Torroella de Montgrí in August 2022, Pagès Jordà was one of the most important intellectuals of contemporary Catalan literature.

He began his career in 1990 with Circles of infinite combinations and he wrote twenty works throughout his life, winning numerous literary awards and obtaining significant recognition, such as the National Culture Prize in 2014.

His literary style was characterized by experimentation, intertextuality and the ability to tell stories that transcend conventional genres. This versatility is evident in The Whist Playersa novel in which the author combines narration, diary and posts on social networks to reconstruct the life of Jordi Recasens, a wedding photographer in the middle of a midlife crisis.

Throughout these pages, we see Recasens facing the issue of her daughter Marta’s wedding to a man known as Bad Boy.

The Whist Players starts like Stand by mecontinue as The bride’s father and culminates in a mix of American Beauty and Mystic River, says the publisher.

In the line of works such as The wild detectives by Roberto Bolaño, Pagès Jordà achieves in this novel one of his highest points as a writer and, as Jordi Amat says in El País, it confirms him as one of the most brilliant prose writers of the Catalan culture of democracy.

Vicenç Pagès Jordà not only left an invaluable literary legacy, but was also actively involved in the promotion of literature. He taught classes at the Ramón Llull University, published reviews in newspapers and conducted writing workshops for decades. His influence on contemporary literature is undeniable and his ability to reinvent the classic novel with a harmonious approach establishes him as a postmodern classicist.

The reissue of The Whist Playersposthumously, gives us the opportunity to appreciate the legacy of an author who challenged the limits of narrative and left an indelible mark on Catalan literature.

Jordi Recasens can go days and days without drinking a single Moritz, he forces himself to smile when he feels like sending a client away, he rubs his skull with minoxidil every night even if he falls asleep, but he can’t stop putting in Start your computer and browse the photolog network before turning off the light. He is aware that this virtual tour keeps him awake, meaning that he has no right to complain if he cannot fall asleep. He starts with his daughter’s photolog—with his heart in his mouth, in case he has posted some ribald photograph—and then he jumps from favorite to favorite, except for those in the Bad Boy circle. It delves into the photologs of Noia Labanda, Sheena, B3rt9, Maldia, Tres Martinis, Dark Princess, Laia4ever, Pink Chameleon, RockStar, PsychoCandy, Blinqui, Le Diclone, Girl in the Mirror, by Anna.K, by Monika_Shift, by Maixenka, in some other chosen at random and, finally, he dives into Halley’s. Oh, Halley, languid and fierce, fragile and energetic, say: when you renew your photographs, doesn’t it occur to you that they give Jordi insomnia? Those fiery nails, that insolent look, those dances without music, those visual poems, that unblemished skin, that face so – unnecessarily – made up, that naive sophistication: Halley in the bathtub, Halley with a hat, Halley in front of the mirror, Halley making faces, Halley on the beach, Halley with lollipop, Halley kissing Sheena, Halley on vacation, Halley with her dog. Halley’s boots, Halley’s hair, Halley’s top. And above all, Jordi, why are you looking at it at that hour? Do you think you’ll go to sleep then? Are you sure it’s the right day? Tomorrow everyone is going to observe and photograph you, and you are going to have dark circles under your eyes that you will be able to remove with a good retouching program, yes, but that will remain engraved in the memories of the guests.

The light from the street lamp sneaks under the door that leads to the street. Jordi has lain down on the futon, in a corner of the garage that he first set up as a photography studio and then as a miniloft. In front of the futon there are shelves full of childhood games, including the giant Palotes castle and the Asterix statuette. On the left, the rotating screen between the two tables: the public and the private, each with its chair, its drawers and its folders. On the other side, the professional area, which includes the printer, the filing cabinets and the negative cabinet. The door at the back leads to a small sink with a built-in shower, the only partition in thirty square meters. In the space now occupied by the sink, Jordi had concentrated the wet area where he had long ago hung, under the red light bulb, the negatives on the Patterson clamps and enlarged the positives with the old Meopta enlarger, solid and cheap as a Skoda. At the end of the nineties he began to digitize the entire process and later he moved the developing carts, the trays, the liquids, the marginator, the enlarger, the entire wet area to the storage room in the hallway (“no one can throw their biography in the “garbage”: was his phrase). When he had enough space left, he redistributed it with a futon that he had brought from a Japanese furniture store on Santa Clara Street in Girona. Over time he ended up adding two of his grandmother Quimeta’s things: the nightstand and the chest of drawers, used as a clothing store.

Years ago, when work piled up, Jordi would lie down on the futon to rest for a while, but over time he had gotten used to spending the night there after arguing with the woman. He found it very uncomfortable to lie next to her in the double bed, in the dark, motionless and tense, waiting for a dream that he knew would resist him. Since his arguments had no end—on the contrary, the possibility of going to sleep in the garage seemed to stimulate them—the futon had ended up becoming his usual resting place. The positive thing was that he was spared the violent awakenings on Sunday, since Michi’s rain of decibels on the living room’s music system was attenuated by the distance. The negative was that, since he slept next to the computer, he had become accustomed to the nightly stroll through Marta’s and her friends’ photo logs, which prevented him from falling asleep. Lying in bed with my eyes closed, I looked at the photos again while listening to the hum of the refrigerator, the clatter of the garbage truck, the dissonant concert offered by the street cats, the howls of the neighbor’s setter, the ringing of bells. of San Pedro, which sounded like falling drops, with the little tail that the drops have at the top, which is like the vibration of the bell when it dies out among the surrounding buildings.

Before 1977, Jordi had had no problems sleeping. He fell flat as soon as he got into bed, both in winter, tired from classes, and in summer, exhausted from walking down the street and playing soccer. He couldn’t hear his parents, the neighbors, the motorcycles with non-approved exhaust pipes, or the television, although only a partition separated him. He had fallen asleep in his mother’s hair salon, lulled by the relentless chatter of the clients and the hum of the dryers. Before ’77 he had no headaches, no insomnia, no obsessions.

Today, on one of those nights of persistent vigil, the images from the photologs mix with the memories of the eighties, of when the three of them slept in the same room, in the apartment on Panissars Street, of when they had already moved from Santa Margarida to Figueres, back then, when they were a family. His wife and him, curled up in the square and a half bed; Marta, just a few days old, in a crib located between the bed and the wall. Every three hours, with self-conscious regularity, Marta claimed her milk ration. At that time his wife was a mammal that maintained excellent relations with biology. She always knew what she should do. Jordi spent the night in a cotton sleeper, hearing in the reassuring background the slow breathing of the female and the creature. The entire world was contained within those four walls. If he woke up, he only had to strain his ears and immediately hear the rhythmic gasps that filled him with placidity and pride. It was winter. No noise bothered him except Marta’s sweet gurgling, the gurgling that that pine nut mouth produced when he slept. He approached the woman’s warm body and they embraced in their sleep while, outside, the wind blew through every corner of the building. At the foot of the bed they had connected a pilot lamp in the shape of a rabbit, which bathed the room in a slight orange light. When the woman breastfed Marta, he glimpsed her bodies in the darkness and turned over to sleep, carried away by a feeling of fullness that he has been unable to recover. Yes, he was also a mammal at that time.

[ad_2]